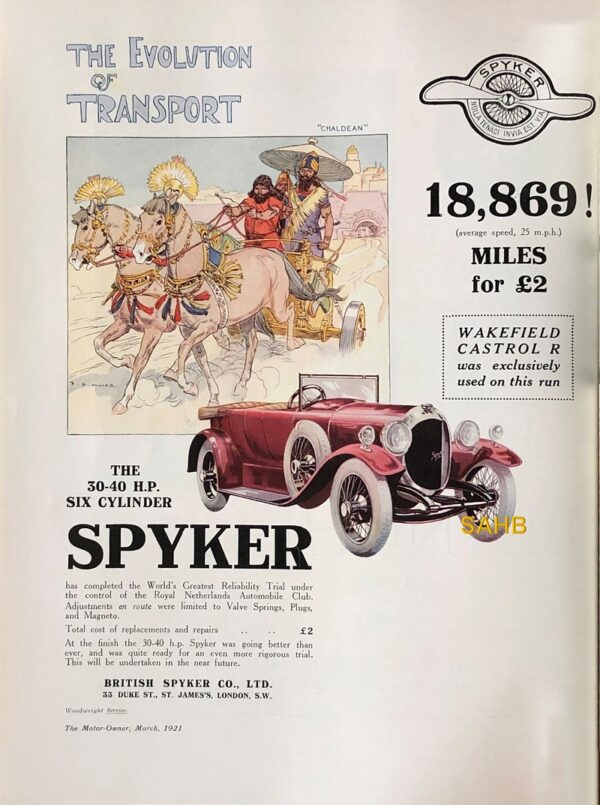

This advertisement was one of several issued by Spyker in 1921 to celebrate a reliability trial. Very little detail is given, but the achievement was genuine: on 27 November 1920 the first Spyker 30-40 H.P. C4 was completed, powered by a 6-cylinder Maybach engine of 5,742cc. The car improved the 15,000-mile long-distance endurance record, held since 1907 by the Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, by some 3,800 miles – and it did this in the Dutch winter weather in just over a month.

Spyker (or Spijker) was founded in 1880 by blacksmiths Jacobus and Hendrik-Jan Spijker. The company built the Golden Coach for state ceremonial use by the Dutch Royal House in 1898. In 1903, Spyker built the 60 H.P. racing car; it was the world’s first four-wheel-drive car, with the first six-cylinder engine and a very early four-wheel braking system. The car survives in the Louwman Museum in Den Haag.

Hendrik-Jan Spijker died in 1907 on his return journey from England when the ferry he was on, the SS Berlin, sank, and this loss led to the bankruptcy of the original company. A group of investors bought the company and restarted production, but Jacobus Spijker was no longer involved.

In 1913, the company was again in financial trouble, and in 1915 was taken over by new owners and renamed Nederlandsche Automobiel en Vliegtuigfabriek Trompenburg (Dutch Car and Aircraft company). A new car, the 13/30 C1, was introduced but sales were not encouraging. The company motto became Nulla Tenaci invia est via, Latin for “For the tenacious no road is impassable” – a motto that can just be seen in the advertisement as part of the Spyker “propeller” logo.

During World War I, in which the Netherlands were neutral, some 100 Spyker fighter aircraft and 200 aircraft engines were produced.

In 1919 Spyker produced the two-seater C1 “Aerocoque”, with aerodynamic bodywork influenced by aircraft design. Although intended as a show car, it was produced on a very limited scale. The car was mainly designed by Jaap Tjaarda van Sterkenburg, brother of John Tjaarda and uncle of Tom Tjaarda, both also car designers.

Spyker continued to break records. In 1922 at Brooklands, Selwyn Edge drove a Spyker C4 fitted with streamlined racing bodywork to a new “Double 12” average world speed record, covering 1,782 miles at an average speed of 75 mph for the 24-hour aggregate of two 12-hour periods.

Sadly, Spyker went bankrupt again in 1922 and was bought by Spyker’s distributor in Britain, who renamed the company Spyker Automobielfabriek. Production continued and prices were reduced, but sales continued to fall, and the company ceased operations in 1926.

Image courtesy of The Richard Roberts Archive: www.richardrobertsarchive.org.uk

According to English motoring reports, the Dutch trial was planned to run for 30,000km (c.19,000 miles) at a rate of about 550 miles per day and 25 mph on a course between Nymegen and Sittard, 220km apart, to be covered back-and-forth 138 times. The engine was supposed to run continuously for the intended five weeks of the trial but did not achieve that due mainly to broken valve springs. An official observer, Mr. W. N. Barker, recorded that the engine was stopped nine times for the fitting of thirteen new valve springs, six sparking plugs and a new Bosch magneto – just £2-worth of failed bought-in components. The car suffered many punctures, a broken windscreen and broken lamp bulbs too and of course, had to replenish oil, fuel and water with the engine running. It did manage the first eleven days without an engine stop, achieving 6000 miles in 280 hours of driving. What impressed motoring journalist Captain Wilfred Gordon-Aston, inspecting the officially opened-up engine, was that even after 30,000km the advanced design of the Spyker’s Maybach combustion chambers had resisted any significant build-up of soot. On that evidence, he wrote, it was good for 100,000 miles before decarbonising.

That early 1921 British Spyker advert intimates the car was soon to be put to further “rigorous trials”. In fact, before the Dutch trial was over, the London press reported that a “continuation trial” was scheduled to follow with the car untouched – one journalist said his contact, Spyker engineer “Kool” Koolhoven, had told him the car was immediately to do another 10,000 miles in Britain. It was reported in London during January 1921 and it then went on a tour, possibly appearing at the Glasgow Motor Show 28th January, certainly giving demonstration runs in Edinburgh and went as far north as Aberdeen where, on 7-8th February, it was on show at Town and Country Garage accompanied by “T. Jarrda of Tromperg [sic] and Frank Eason of Spyker London”, there to answer questions and give demonstration runs. All suggesting that the Netherlands trial and UK continuation were commissioned by the British Spyker Company.

At the time there was an English financial, possibly managerial, connection between the troubled Spyker Company and another car company destined to fail in that decade: Angus Sanderson (A-S). When Selwyn Edge drove the Spyker to its double-twelve record, general manager of Spyker, London was Lieut. Colonel Sam Janson who, as a protégée of Edge, had first worked for him at Gladiator and then at Napier, where he became a director and then MD of Hertford Street Motors, a Napier and Electromobile dealership. In 1913, he tried his hand at making his own Janson 18-22 h.p. torpedo-bodied car but WWI intervened and his unsold cars went to the War Office when he was commissioned in the Army Service Corps in October 1914. He served with distinction in France and later joined the newly formed RAF, controlling its UK transport but before demob was involved in a 1919 WRAF officer scandal.

Janson was working for A-S when at the end of 1920 it was declared bankrupt and refinanced largely by Mr G. E. Ostwalt, Managing Director of the British Spyker Company Ltd., 33 Duke Street, St. James’s, London, with funds approaching £240,000 from “overseas sources” and A-S dealers. Initially Ostwalt, Janson, J. E. Price of A-S and H. T. White of Tyler Engines were directors of Ostwalt Limited, A-S’s new and short-lived parent company. One reported proposal was that Spyker and A-S cars would be made at the Tylor Engine factory in New Southgate but this and much more in the A-S recovery and manufacturing plan wasn’t enacted – Price took over management of a new Angus Sanderson Ltd. based at Hendon and Ostwalt disappeared from company reports.

Meanwhile, by special arrangement, Janson worked as general sales manager to promote British Spyker, which he did by advertising and organising tours and trials. After a tour, which started in August 1921 and continued until at least October, he was fined £10 plus costs in Warwick in November for driving a Spyker which still displayed a Netherlands index mark, “N.L.G.17014”, but no British revenue license – the prosecution claimed the Treasury had been defrauded of £9. Janson complained that this Spyker had been driven all over Britain that year and only Warwick authorities had raised a summons. It seems this was not the Netherlands test car; a photo said to show the drivers in the original Netherlands’ test car shows it to be G10898 and except for the addition of an extra spot-light and two pennants by the headlights, this C4 looks like the same one that appeared in British press photos in January 1921, although its number can’t be seen.

Surely then, it was Janson who encouraged, even sponsored, the 54-year-old Edge to attempt to break his 6-cylinder Napier’s 1907 Brooklands records using a 6-cylinder Spyker on 19th and 20th July 1922. And no coincidence either that alongside Edge’s successful Spyker record attempt, Janson’s well-known ex-WRAF driving instructor and motorcyclist wife, Gwenda Marie (nee Glubb and the later remarried, Montlhery record-breaker, Mrs. G. M. Stewart), also broke two world records on her 250cc, 2¼ h.p. Trump-Jap motorcycle, riding nearly 1072 miles during the same “double-twelve” at an average speed of c.45 mph – impressive, compared to Edge’s c.75 mph/1782 miles with 5742cc and 30-40 h.p.

Interestingly, before all this, at least one of the limited production Spyker Aerocoques came to Britain, it being displayed on the Hughes Motor Engineering Company’s stand at the Glasgow Motor Show in January 1920. Appropriately, given its design, the show car had already been purchased for £1650 by Major H. G. Hawker, the Australian ex-Sopwith test-pilot, almost first Atlantic flyer and company founder. At that time, no more Aerocoques were expected to be available for at least ten weeks, perhaps no more were. Hawker died in a Hendon plane crash a year later.

As to the Spyker company’s demise, its reported 1921 manufacturing plan for Trompenberg was to make 100 cars per month but because the C4’s 20,000 florins price was considered too high for all but a few Dutch motorists, a licence to make a c.1170cc, 4-cylinder Mathis car was reported signed in July 1921. Motor show reports in January 1922 confirmed Spyker output remained small but supposedly “a plan was in place to meet British and Colonial needs” – this was presumably down to Spyker London’s influence. The press duly noted that Trompenberg factory was financially re-organised in July 1922 after suspending payment to creditors but commercial reports in 1923 said that the factory was still making C4 cars and was very busy producing 2-ton lorries “a year after its re-organisation [and] notwithstanding the depression in the country”. By 1924, the London company advertising was N. V. Spyker Limited, Duke Street, which had another car/commercial sales office at 4, Palace Street, Westminster but it “disappeared” during 1925, presumably with no new Trompenberg-built vehicles to sell.

Seems that Col. Sam Janson gave up cars too; a landlord of that name was later running the Old Crown beer house in Much Hadham, Herts.