There were four Columbia car manufacturers, all of them in the United States, but this one, built in Hartford, Connecticut, was the best known – so much so that a rival in Detroit changed its name to Columbian almost immediately after its creation in 1914 to avoid confusion, even though the Hartford-based original had closed in 1913.

The original Columbia company was started in 1897 as Pope Manufacturing Company. Colonel Albert Augustus Pope made bicycles from 1877, and by 1899 he had formed the American Bicycle Co., a conglomerate controlling 45 manufacturers. Pope was not an engineer; he turned to others to design for him, including Hiram Percy Maxim, son of the inventor of the machine gun, who arrived in 1897 and created a range of electric vehicles, from a light 2-seater to a 12-seater omnibus, since Pope reckoned that these vehicles could easily be recharged from electric light stations that were available in virtually every American town of any size. He did, however, offer some petrol-powered cars from 1899 – just in case.

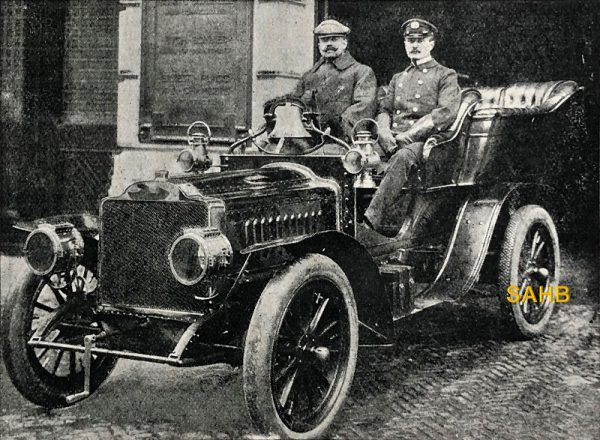

Hiram Maxim left Pope in 1902, and Frederick A. Law became the engineer responsible for the design of a new series of petrol cars. There was still a focus on electric vehicles: in 1902 there were 20 electric cars and only one petrol car in the range – a 12/14hp 2-cylinder. A 4-cylinder 30/35hp car was added in the following year and, judging by its size, the car in our Snapshot is almost certainly one of these.

By 1907 there were seven petrol and only eight electric models in the range, and the last electric was listed in 1911. The demise of the company was brought about by a grandiose scheme, Briscoe’s United States Motor Company – but that is another story. Pope had left Columbia in 1903 to form Pope-Hartford.

The man in the uniform, said to be the owner of this Columbia, is the renowned fire chief of New York Edward F. Croker, a pioneer in creating laws to safeguard against fire hazards. He stated that the simplest way to prevent fire death is the simple drill. Knowing the location of exits and the use of clear signs and directions (which seem obvious today) were radical ideas at the beginning of the 20th century. In a city filled with immigrants without a common language, the giving and following of directions was not a simple task. For this reason, Croker proposed that, “…all instructions for fire drills should be printed in the language of the majority of the workers in a given shop; in two or three languages if necessary, in addition to English.” He recommended training a manager to take charge, and teaching workers how to behave in a calm and orderly fashion in the event of a potentially dangerous situation. He also suggested alternatives for constructing fireproof buildings, such as eliminating all wood and using metal, terra cotta, or concrete, and for establishing adequate exit routes. His ideas were the foundation of the Fire Prevention Law of 1911.

Image courtesy of The Richard Roberts Archive: www.richardrobertsarchive.org.uk

Leave a Comment