Thunderbolt was the largest, fastest and most powerful Bean car ever built. This deserves an explanation.

Capt George Edward Thomas Eyston was born on 28 June 1897 and died on 11 June 1979. Following distinguished service in World War I he read engineering at Cambridge. He made his early living as a racing driver, most successfully with Aston Martin. After a short period racing boats, he returned to four wheels, buying Malcolm Campbell’s Bugatti and setting out on a lucrative racing career in a variety of cars.

His record-breaking exploits were mainly focused on endurance – and he pursued them in cars as varied as an 8-litre sleeve-valve Panhard, the ‘Safety Special’ (a Chrysler chassis powered by a 9-litre AEC diesel bus engine) and ‘Speed of the Wind’ (powered by a 21-litre Rolls-Royce Kestrel aero engine). In 1935, Eyston was at Bonneville with ‘Speed of the Wind’ on the same day that Campbell was running Blue Bird. Campbell achieved his aim of breaking the 300-mph barrier: he took the Land Speed Record at 301.13 mph.

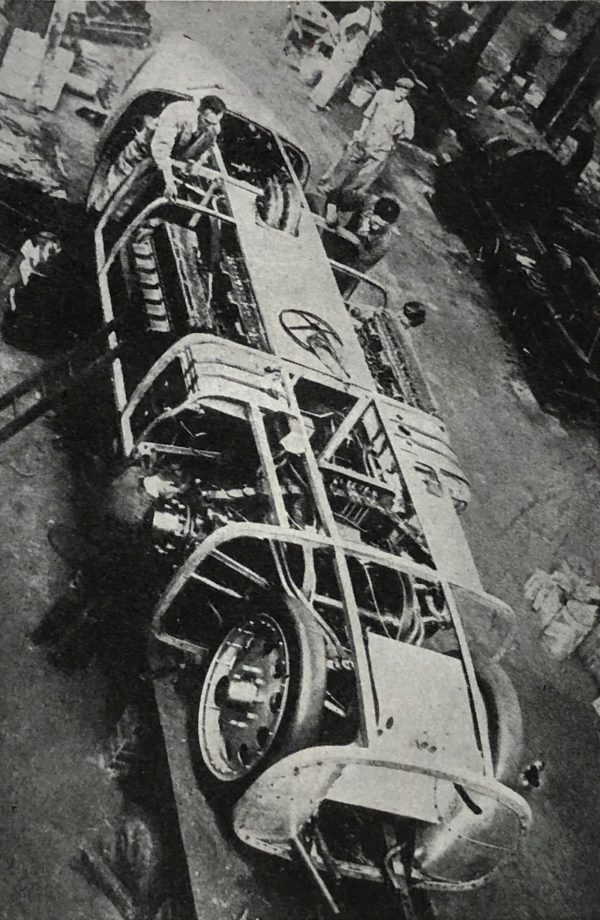

Eyston learned much from Campbell’s efforts, in particular the importance of stability at high speed (Campbell’s car had suffered from some lurid skids during the successful attempt). From 1936 Eyston therefore set out to break the record with his own car. Eyston contracted Beans Industries in Tipton, Staffordshire, to build the car. They were a good choice: skilled general engineers, at that time making front axles for ERA cars, Gough engines for sports cars and Cotal electric transmissions under licence.

The car used a conventional pair of parallel beams from which hung all the parts. Suspension was independent all round, by transverse leaf springs. Steering, built by Wolseley, was complex, with two sets of front wheels of different tracks, independently sprung by tubular wishbones. The first pair were unbraked, but the second pair had shaft-driven inboard disc brakes, designed and patented by Eyston jointly with Ferodo and probably made by Borg & Beck. They were operated by Lockheed hydraulics. The twin rear wheels were braked by a pair of discs on the rearward extension of the main drive shaft. The brakes were only for use below 180 mph, with hydraulically-operated air brakes used for higher speeds. Thunderbolt was powered by two Rolls-Royce ‘R’ Type V-12 engines, each of 36.5 litres capacity, mounted side by side amidships, behind the driver. Each had its own clutch and drove into its respective side of the 3-speed gearbox.

The car was shipped to Bonneville at the end of August 1937 to catch the period when the salt flats would have a dry crust, but conditions in 1937 were poor: the salt bed was still covered by floods from the previous winter. Only on 28 October was Thunderbolt able to run for the first time – but what a run! 309.6 mph over the mile, 8 mph faster than Campbell ‘s existing record.

Gearbox problems precluded a return run, as they did after repairs on 6 November when once again a fast run – of 310.69 mph – could not be followed by the essential return stint. Eyston and his team found a solution, telephoned Offenhauser in Los Angeles to describe what he needed and had new parts delivered within a few days.

At last, on 19 November, Thunderbolt was ready. The outward run achieved 305 mph; refuelling and changing tyres took 16 minutes, and despite a scare when a rag left in the cockpit flew into Eyston’s goggles and knocked them up, blinding him temporarily, Eyston kept at full throttle and posted 319 mph (km) and 317.74 (mile) and an average 2-way speed of 312 mph (km) and 311.42 (mile). A new World Land Speed Record.

Eyston was sure that he could achieve more. After extensive modifications at Beans he returned to Bonneville and on 27 August 1938 raised his existing record to 345.21 mph for the mile. Eyston, however, now had severe competition: John Cobb’s Railton was at Bonneville, and on 15 September raised the record to 350.2 mph for the kilometre. But Eyston finally took the record for the third and last time the following day, at 357.5 mph for the kilometre.

Picture courtesy of the Richard Roberts Archive

Leave a Comment