Way back in Snapshot 74 appeared the 1903 Chainless car built in Paris. Its main interest lay in the source of many of its chassis components: Messrs Lacoste & Battmann, also of Paris. L&B kits came in various sizes and appearances and were especially popular among small manufacturers (or “assemblers”) between 1902 and 1907.

The Speedwell, built between 1900 and 1908, initially in Reading and then in London, was one of the British cars that contained many elements from Lacoste & Battmann. Speedwell Motor & Engineering Co. Ltd. were originally agents and factors in the cycle trade. Before 1900 they diversified into the sale of cars, advertising popular models such as Renault, Léon Bollée, De Dion-Bouton, MMC and Gardner-Serpollet. The owners, the Dew family, built a Rochet-based special, and the name Speedwell first appeared on a few Hanzer cars that they imported from France. From around 1902 the first British-built Speedwells appeared, with L&B chassis and De Dion engines. Five chassis were available at the 1903 Crystal Palace show, from 6 h.p. to 40 h.p.

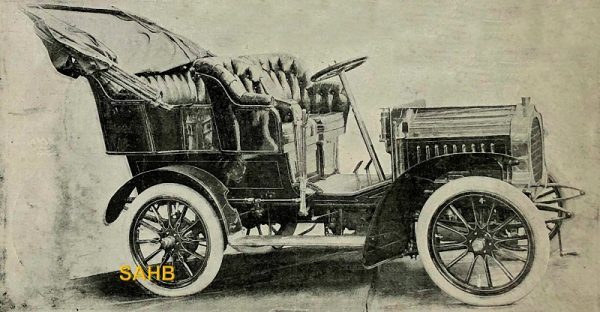

The 10 h.p. model in our latest Snapshot dates from 1905, by which time Speedwells had started to commission their own castings for axles and gearbox parts. At this point, too, the distinctive round radiator replaced the earlier square version. The 10 h.p. was powered by a twin-cylinder vertical Gnome engine. An article in The Motor for 18 April 1905 praised the 10 h.p. as a ‘Cheap and Thoroughly Well-designed Vehicle’, but there were no outstanding attributes to set the car apart from the multitude of similar cars of the time – apart from one.

This was the gearbox. Whether or not Speedwell had designed all or part of it, a remarkable feature was that in direct-drive top gear “all the gear wheels are out of action, thus reducing the wear and friction to a minimum.” An illustration of the gearbox internals suggests that the dogs on the front of the sliding gearset not only engaged direct drive but also took the rear-mounted constant-mesh layshaft gears out of engagement, thus making them and the layshaft stationary. This, if true, would be a far simpler arrangement than the 1914 Le Gui transmission in our own Technical Talk No. 1, which can be found in our ‘News’ column.

By 1906 the company had been taken over by Brown Brothers and was therefore once more mainly concerned with factoring and agencies. New models with Aster engines were on display at Olympia in 1907, but sales must have been poor because the Speedwell disappeared soon after.

Image courtesy of The Richard Roberts Archive: www.richardrobertsarchive.org.uk

The Speedwell was not uniquely remarkable as it was not the only British car built that year with a sliding pinion gearbox in which the layshaft was static when in direct drive.

Another, on show at the Agricultural Hall Motor Show in Islington in March 1905, was the Coronet Motor Company of Coventry’s new 4-cylinder 16-h.p. car. They claimed it was “All British”, using only a few bought-in ancillary components. Walter James Iden was the designer of the car, if not specifically its gearbox. Any connection with Speedwell seems unlikely, as Coronet (established with Walter Perkins in 1903) went out of business in December 1905.

The car’s transmission was described in a report in the Field Magazine of May 6, 1905: “Next comes the gearbox, which presents an ingenious arrangement. The car has three speeds and reverse. On the top speed, the drive is direct, and the secondary shaft is set free, so that it does not revolve at all. This is contrived by mounting the gear wheel, A, freely on a bearing on the shaft, B, so that it only transmits motion when the jaw clutches, C, on its face are engaged with the similar clutches, D. This it does when first and second speeds are engaged. When the top gear is in action the clutches, CC, are withdrawn, and although A is still partly in mesh with the fixed pinion, F, on the secondary shaft, it merely allows the primary shaft to rotate freely through it, and consequently the secondary shaft is at rest. The driving connection on the top speed between two portions of the shaft, B, is secured by means of jaw clutches on the face of the gearwheel, F. Gear changing is facilitated on the Coronet car by means of a clutch-check which reduces the rate of revolutions of the shaft while the new speed is being introduced. A universally jointed Cardan shaft conveys the drive from the gearbox to the live rear axle. […] The change speed is by the usual lever working in a notched quadrant.”

Hence, at that time neither were unique but despite the proclaimed benefits of reduced noise, friction and wear with a static layshaft, a motor show correspondent in 1908 noted that by then very few cars had one – of the better-known firms Martini and Napier, at least, did. Apart from needing to overcome problems re-engaging rotating and static gears (note Coronet’s main-shaft “clutch check”), the delay in its wider development and adoption was suggested to be caused during 1905-7 when gearbox makers had been threatened with prosecution by arch transmission innovator Louis Renault for infringing his 1899 French master patent, which had first defined the principle of “direct drive” and “sliding pinions”. In 1905, ten French companies chose to pay Renault Frères royalties to avoid litigation but in the UK Renault’s case was appealed to the Lords and it was 1907 before they could claim their dues.