Introduction

The wonderful thing about catalogues of commercial vehicles is that they are promoting the machine to hard-headed business owners who need to know how it will improve the profitability and reputation of their business. So it is with this catalogue, reputedly from 1916.

The Autocar Company was originally called the Pittsburgh Motor Vehicle Company when started in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1897 but was renamed the Autocar Company in 1899 when it moved to Ardmore, Pennsylvania. By 1907, the company had decided to concentrate on commercial vehicles and the last car was built in 1911. The Autocar name is still in use for commercial trucks.

Its founder Louis Semple Clarke (1867–1957) was a successful mechanical engineer. Among his innovations were the spark plug for petrol engines and a driveshaft system for motor cars. Clarke developed the first porcelain-insulated spark plugs in America; the Autocar thread specification became the standard in the U.S. automotive industry.

This innovative streak is evident throughout the Autocar catalogue; here are some of the more important features and how their benefits were sold to potential customers…

A host of advantages

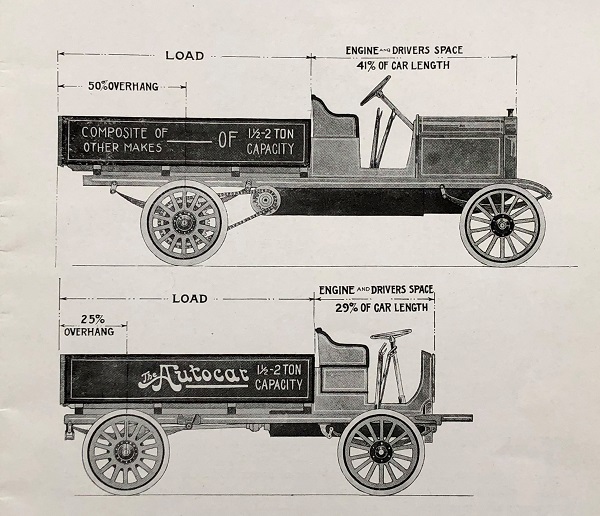

Fig 1 appears in the catalogue under the heading “COMPARATIVE DIAGRAM”. In the upper picture, the engine and driver’s space is 41% of the vehicle’s length. The waste of space is evident. As a result, there is a 50% overhang of the load over the rear axle. The lower picture demonstrates the Autocar’s advantages: the engine mounted under the seat makes the front far more compact, taking up only 29% of total length. The load overhang is only 25%.

The text under this picture is succinct and convincing:

“The body sets well forward on the Autocar chassis so that the live load is evenly distributed and puts no excessive strain on any one part. This equality of weight distribution is a material factor in saving tire wear.

“The shortness of the Autocar overall saves very materially in garaging space, and makes it possible to load and unload in narrow places. In crowded traffic the Autocar is exceptionally easy to handle and can be driven at a greater average speed than a longer car could maintain.”

Shown, but not mentioned in the text on this page, is the comparison between the chain drive of the competitors and the shaft drive of the Autocar. This comes elsewhere in the catalogue (see below).

Fig 1. The comparative diagram. Commercial customers would immediately understand the greater utility and therefore profitability of a truck with lower tyre wear, less strain on key parts, and greater speed and manoeuvrability.

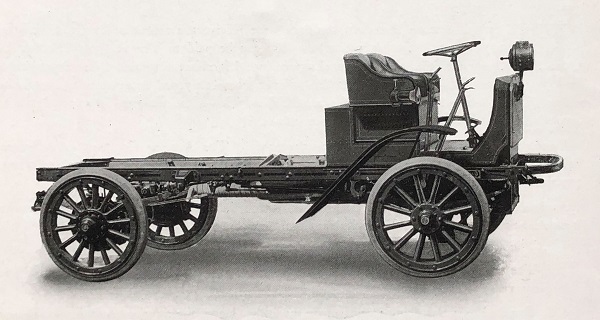

Easy access to the engine

Figs 3 and 4 show two views of the standard Autocar truck. Fig 3 is a view with “seat structure in normal or lowered position.” Fig 4 demonstrates how simple it is to access the engine. The caption reads: “The hinged metal seat structure is an exclusive Autocar feature – it gives instant access to the motor”. The text is even more positive: “The seat can be raised with one hand by means of a spring balanced system of levers.”

Fig 3. Normal view

Fig 4. A picture is worth a thousand words: how to access the engine.

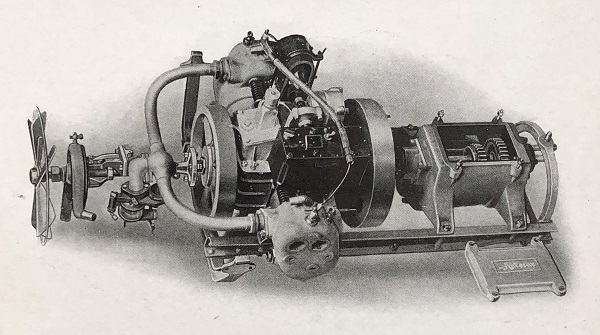

The engine

The engine fitted neatly under the seat and had many appealing features. It was a four-stroke two-cylinder unit with opposed pistons; the twin flywheels ensured smooth operation. Lubrication was by force-feed oiler to a splash pan under the connecting rods – and a hand pump on the dashboard allowed extra oil to be supplied “under abnormal conditions.”

Fig 5. The engine – mounted longitudinally under the seat.

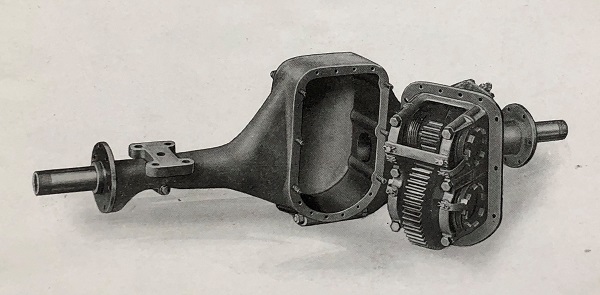

The rear axle

This unit was perhaps the most innovative of all. Firstly, it was fully floating: the wheels were mounted on tapered roller bearings, meaning that the drive shafts were subjected neither to vertical loading of the truck nor to transverse loading from shocks or cornering forces. They simply took the strain of driving the wheels. Secondly, it was a double-reduction axle. This not only gave a total of 7.1:1 reduction through the bevel and spur gears, thus giving “low reductions without the sacrifice of road clearance” – but it also reduced the angularity of the propeller shaft, “giving straight lines for the transmission of power.” These advantages were amply demonstrated in the opened-up view in Fig 6: the flange for the attachment of the wheel bearing is evident on the left (the protruding splined half-shaft merely had to drive); the classic bevel-gear drive is hidden, but the reduction gear is shown clearly – taking the drive down to the axle line, and thus keeping the propeller shaft high up at the level of the engine’s axis.

Fig 6. The rear axle – fully floating and double-reduction.

A persuasive proposition

With just a few well-chosen images and a succinct text, the Autocar gave a powerful argument to the customer who needed a truck that was sturdy, go-anywhere, reliable and therefore a profitable tool for their distribution and delivery business. The rest of the catalogue is full of small photographs of Autocar trucks in use by a vast range of American companies, accompanied by a long list of their names. This would have been a highly effective piece of promotional material.

Images courtesy of the Richard Roberts Archive

Leave a Comment