The search for silence in early motor cars was not just a battle against noise; motor engineers understood that noise meant stolen energy and stolen energy meant wear.

The 1914 8 h.p. Le Gui, manufactured in Courbevoie near Paris, was in most respects a conventional machine, powered by a 1,600cc side-valve 4-cylinder engine from Decolange – as were contemporary cars from Sizaire-Berwick. But its gearbox was far from the ordinary.

A conventional gearbox of the day would have an input shaft, permanently geared at the entrance of the box to a layshaft carrying gears of varying ratios. The output shaft, concentric with the input shaft, would carry sliding gears, moved by selector forks, that would mesh with the layshaft gears to give these varying ratios – except in top gear, when a dog clutch on the output shaft would engage with the input shaft to give direct drive.

The problem that Le Gui aimed to overcome was that the layshaft was always rotating even when the car was in neutral or in direct drive – causing noise and energy loss from the initial drive gears and bearings of the layshaft, and eventual unnecessary wear.

Le Gui’s solution was to allow the initial drive gear on the layshaft to slide: into mesh with the initial drive gear on the input shaft only when needed for the three intermediate speeds, and out of mesh in neutral or in direct top (fourth) gear. The reduction in noise, energy loss and wear is evident.

The mechanism to achieve this was a spring that held the sliding layshaft gear out of mesh. Each intermediate sliding gear unit on the main output shaft had an additional finger that pushed the layshaft gear into mesh. To achieve a smooth change, the layshaft gear engaged first, followed by the chosen gear on the main shaft.

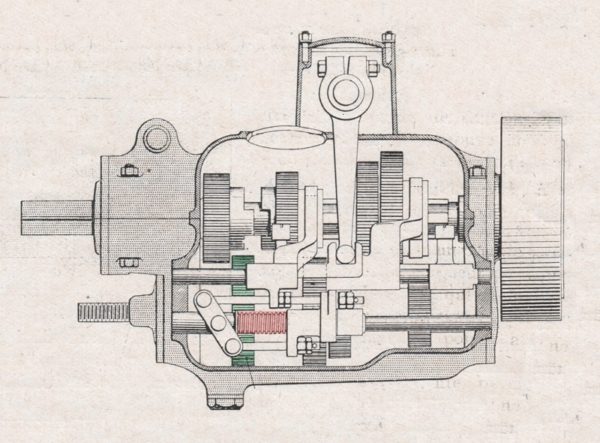

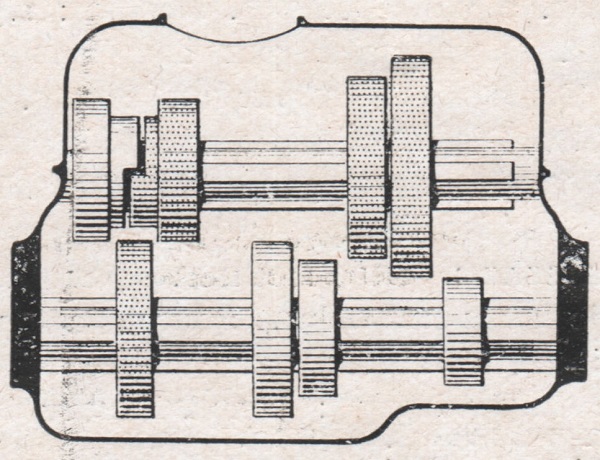

In the headline sectional drawing above, the drive from the engine is on the left and the output to the rear axle on the right. The drawing is very busy – and the other two sections that we have not shown are even more challenging to interpret. But at least we can see the all-important spring (in red) that holds the layshaft gear (in green) out of engagement until first, second or third gear selection pushes it. The rocker just to the left of the spring, and the various bars and stops, are the mechanism that always moves the layshaft gear into mesh when needed, regardless of whether the sliding gear units move left or right.

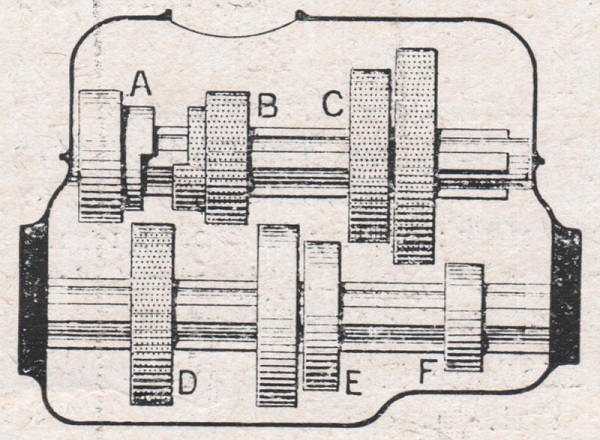

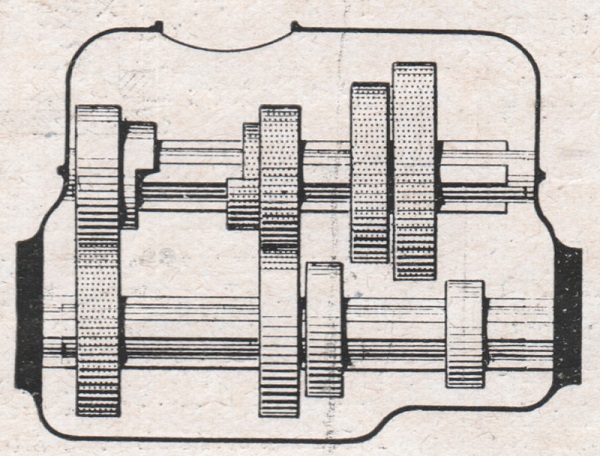

Fortunately, the article’s author (or Le Gui’s drawing office) helpfully provided three small diagrams, without the selector forks, fingers or spring – and these diagrams explain the principle. Here they are:

Neutral. The layshaft gear D (lower left) is held by a spring out of mesh with the input drive gear A – so the layshaft is stationary and silent. The remaining gears are conventional: B slides left for direct top or right for third; C slides left for second or right for first. E and F are fixed on the layshaft.

Third gear. Layshaft gear D is pushed left against its spring to engage with A, so the layshaft now rotates, and B is pushed right to mesh with E.

Top gear (direct drive). Layshaft gear D is held out of mesh again by its spring, and B moves left to engage with A through a simple dog clutch. The layshaft is again stationary and silent.

The article, in the 9 May 1914 issue of the French magazine Omnia, was full of praise for this innovation. Sadly, it did Le Gui no good. The company ceased manufacture in 1916.

Drawings courtesy of the Richard Roberts Archive

Leave a Comment